Neurodiversity Toolkit

How to use this toolkit

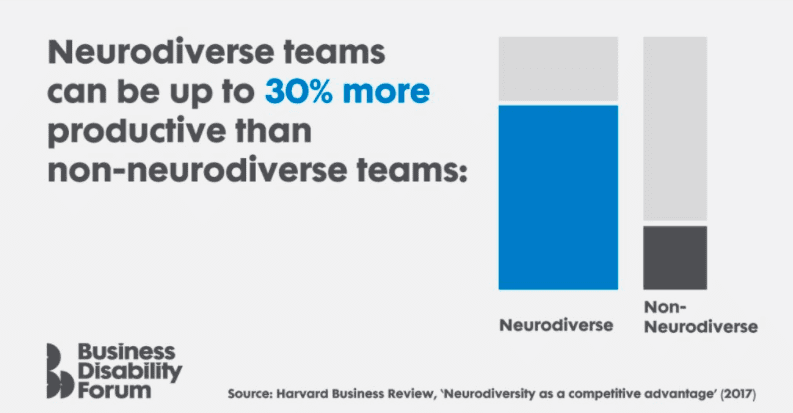

This toolkit is designed to support services and managers in relation to neurodiversity and to have quality and informed conversations. It will help managers to be supportive and to ensure an inclusive environment which harnesses the unique strengths people with neurodiverse conditions can bring.

Conditions may include: dyslexia, dyspraxia, dyscalculia, dysgraphia, Meares-Irlen Syndrome, Hyperlexia, Tourette Syndrome, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Synaesthesia and Stammer.

The toolkit provides links to widely available sources, jargon buster, practical tips for managers and a simple test to find out if you have specific neurodiverse characteristics.

You will learn what line managers can do to help neurodiverse staff and help them understand what these conditions are and how they can help. It also provides more detail about specific work settings and helps staff with these conditions to articulate to their management what challenges they face and how they can help. It also includes practical advice about reasonable adjustments and associated workplace passports.

Disability Risk Assessment needs to be completed or needs to be included within reasonable adjustments for members of staff.

The aim is to celebrate neurodiversity, strengthen networks, support staff and increase awareness of these conditions.

What is Neurodiversity?

Neurodiversity – definition

“The range of differences in individual brain function and behavioural traits, regarded as part of normal variation in the human population.” 1

Neurodiversity – The diversity or variation of cognitive functioning in humans.

Neurodiverse – Inclusion of a number of substantial cognitive functioning variations.

Neurodivergent – Having a less-typical, cognitive variation, such as Autism or ADHD.

Neurodivergence – The presence, or grouping, of less-typical, cognitive variations.

Neurodiversity is representative of the fact that differences in neurology should be recognised and respected as a social category, similar to ethnicity, socioeconomic class, sexual orientation, gender or disability (Judy Singer, 1990). Originally used to describe behaviours from within the autistic spectrum, neurodiversity now recognises the concept that all humans vary in terms of our thinking and behaviour. People whose brains work differently, for example, because of conditions such as autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or dyslexia may need support.

Neurodiverse people’s abilities vary; strengths and weaknesses can be more pronounced, tending to lead to inconsistent performance at school or work. However, abilities and skills expressed across a range of areas and activities can sometimes be very easy or equally challenging, with weakness highlighted. The variation for some people can be vast and disabling.

Legislation

Equality Act 2010

The Equality Act 2010 legally protects people from discrimination in the workplace and in wider society. It replaced previous anti-discrimination laws with a single Act, making the law easier to understand and strengthening protection in some situations. It sets out the different ways in which it’s unlawful to treat someone.

You can find out more about who is protected from discrimination, the types of discrimination under the law, and what action you can take if you feel you’ve been unfairly discriminated against.

The Disability Discrimination Act 1995 (Northern Ireland only)

It is an Act to make it unlawful to discriminate against disabled persons in connection with employment, the provision of goods, facilities and services or the disposal or management of premises; to make provision for the employment of disabled persons; and to establish a National Disability Council.

Employees may have the confidence to disclose Dyslexia, but some may fear ridicule. The best practice advice for how to handle candidates with dyslexia in aptitude and other tests can be found on the British Dyslexia Association website, including:

- Dyslexia should be considered in the design of all tests.

- Discuss with dyslexic applicants in advance so that necessary adjustments can be made.

- Ensure that test instructions are clearly read aloud.

- Allow more time for dyslexic candidates.

- Be prepared to waive the test, as there are often equally satisfactory ways of getting the information.

What are dyslexia, dyspraxia, dyscalculia and dysgraphia

- These diagnoses can be classed, in legislation, as disabilities due to the impact they have.

- They may have more than one diagnosis, alongside other conditions, but it is also possible many people have these conditions but have not been diagnosed.

- It’s possible that even with a diagnosis, they may still not have a full explanation or understanding of the strengths and challenges of the condition/s.

- While diagnoses of dyslexia, dyspraxia, dyscalculia and dysgraphia have a lot in common, there are differences across these conditions. Full definitions are included in Annex A.

Dyslexia

The word Dyslexia comes from the Greek, meaning difficulty with words. It isn’t a single medical condition. The causes of the communication difficulties experienced by people with Dyslexia are varied and often hard to identify or poorly understood.

What is dyslexia?

Dyslexia is neurologically based and affects people of any age or background. The difficulties it causes can be managed with appropriate intervention and specialist support. Dyslexia affects more than just literacy – it can also cause problems with short-term memory and with tasks that involve using sequences.

Many dyslexic people experience detriment in their careers because they are perceived as having low intelligence. Dyslexia does not affect intelligence, and employees with dyslexia bring as much benefit to the workplace as any other employee – additionally, people who have dyslexia often excel in lateral thinking and problem-solving skills.

Definition of dyslexia

Dyslexia is a learning difficulty that primarily affects the skills involved in accurate and fluent word reading and spelling. Characteristic features of dyslexia are difficulties in phonological awareness, verbal memory and verbal processing speed.1

Dyslexia occurs across the range of intellectual abilities. It is best thought of as a continuum, not a distinct category, and there are no clear cut-off points. Identifying and Teaching Children and Young People with Dyslexia and Literacy Difficulties. Co-occurring difficulties may be seen in aspects of language, motor coordination, mental calculation, concentration and personal organisation, but these are not, by themselves, markers of dyslexia.

A good indication of the severity and persistence of dyslexic difficulties can be gained by examining how the individual responds or has responded to well-founded intervention.

UK DCD descriptor (2018) DIDA (2018) From ‘Diagnostic Interview for DCD in Adults v.1.8 (DIDA)’: “Developmental coordination disorder (DCD), also known as dyspraxia in the UK, is a common disorder affecting movement and coordination in children, young people and adults with symptoms present since childhood.”

DCD is distinct from other motor disorders such as cerebral palsy and stroke, and occurs across the range of intellectual abilities. This lifelong condition is recognised by international organisations, including the World Health Organisation. A person’s coordination difficulties affect their functioning of everyday skills and participation in education, work, and leisure activities.

Difficulties may vary in their presentation and these may also change over time depending on environmental demands, life experience, and the support given. It may be difficult for someone with DCD to learn new skills. The movement and coordination difficulties often persist in adulthood, although non-motor difficulties may become more prominent as expectations and demands change over time.

A range of co-occurring difficulties can have a substantial adverse impact on a person’s mental and physical health, and create difficulties with: time management, planning, personal organisation and social skills.

With appropriate recognition, reasonable adjustments, support, and strategies in place, people with DCD can be very successful in their lives.

Dyslexia Workplace Assistance and Reasonable Adjustment

Reasonable adjustments are the steps taken to help an individual gain the most of their strengths and minimise the challenges that they might experience as a result of their dyslexia. These adjustments will vary according to the needs of the employee and the job role. An employee does not need to have had a diagnostic assessment in order to receive reasonable adjustments. It is advised that specialist advice, such as a Workplace Needs Assessment, is taken to determine the most appropriate adjustments for a particular individual.

The British Dyslexia association provides further guidance, How can I support my dyslexic employees?

Provision of training programmes/briefings/presentations

It is recommended that all training courses, briefings and/or presentations should be considered in terms of the impact they will have on individuals with Dyslexia.

Presentations and instructional methods should incorporate multisensory techniques – in other words, diagrams and colour should be used to supplement written or verbal explanations as much as possible; demonstrations (‘of how it should be done’) and practice (to encourage learning and skill development) should also be incorporated.

The degree to which dyslexia causes problems, in learning and in everyday life, depends on many factors. These include the severity of the dyslexia, the other strengths and abilities that a person has, and the kind of teaching and support they may have been given.

Information Communication Technology (ICT) has also increased the learning needs of Service employees; individual training records, fire and incident reports, IRMPs, data management and everyday administration work requires the use of computers and software programmes on a daily basis.

For years, the sector has been delivering training in a very prescriptive manner within training and development centres and on the station / watch. The terminology for this sort of learning delivery is simply known as the sheep-dip approach. It did not take account of learning styles (the way individuals learn), learning difficulties (whether literacy or numeracy) or identify issues. Case in point, people with visual or hearing impairments have to learn in a totally different way to those with normal sensory awareness, and the same applies to people with Dyslexia.

Provision of written materials

Any written materials should be considered in terms of their impact on Dyslexia policy documents, procedures, rules, regulations, etc. All need logical presentation, structuring and good printed text should not be justified on the right side. Important points should be highlighted. Avoid underlining where possible. Summaries should be included.

Readability levels and reading speed needs to be considered, unnecessary jargon or uncommon words should not be used, although technical language is necessary and, through repetition, can make reading more manageable. Use bullet points or numbers rather than continuous text (see 17.8 and 17.9).

The provision of information on coloured paper helps, light blue or yellow paper tends to work best. Black on white paper can be especially challenging on the eyes. When using PowerPoint, use light pastel colours for the background.

There is a wide range of PC hardware and software, as well as several handheld devices that are specifically designed to make life easier for people with dyslexia. These are all included within the heading of Assistive Technology.

Examples of the technology that may be suitable for people of all ages are provided below:

Speech recognition software

This allows users to dictate or talk to a computer that uses software to convert this to text. This is clearly of interest to individuals that might otherwise have difficulty with spelling or writing emails, reports or other written communications.

Text-to-speech software

This allows individuals to understand written material they are presented with and to proofread or check their own work.

Mind mapping software

This is specifically designed to allow dyslexics to plan their work more effectively.

Scanning software and hand reading pens

These allow the user to store and listen to the text found in books and other documents.

Spell checkers that are specifically designed with dyslexia in mind

To automatically make corrections to written communications.

Smartpens

These can be used to write text, but which track the text being written and recreate the notes in digital form. The pen can then upload the text to a smart phone, PC or tablet to allow further processing or electronic distribution.

Tablets, Smartphones and Applications

There is a wide range of hardware platforms and software applications that can help individuals to manage their time and task list more effectively or work in conjunction with other hardware devices such as smart pens.

Computer-based learning programs

These are specifically written for dyslexics and can help to sharpen their skills in reading, writing, touch-typing and numeracy.

Colorimetry – special glasses

Coloured overlays can improve reading speed and accuracy. They can enable longer periods of reading free of discomfort. When they do, it is an indication that the individual may benefit from Precision Tinted Lenses. The lenses are prescribed using specialist equipment called a Colorimeter.

Instructions during meeting

- Confirm action point one at a time if necessary, or provide concise and direct instructions to other personnel.

- Provide clear, detailed communication in a project plan format to ensure there is no misunderstanding.

- Demonstrate and supervise tasks and information to confirm understanding is correct with all involved, and have management confirm action to be taken.

- Systematic drawing out from start to completion all tasks or instructions by writing or detailed diagrams (mind mapping).

- Use Dictaphone, where appropriate and safe to do so, to record important instructions or notes to ensure notes are correct.

Any difficulty with reading and writing is overcome by:

- Allowing plenty of time to read any documents and complete tasks.

- Provide copies of materials well in advance of a session.

- Give out relevant abbreviations, acronyms and specialist vocabulary before the session.

- Allow opportunities for enhanced note-taking, including voice recordings of sessions, the use of a laptop or admin staff to assist with note-taking.

- Provide clear verbal and written instructions.

- Prioritise, sequence or list tasks.

- Give adequate time to complete reading or writing tasks.

- Provide an overview of main points and sum up frequently.

- Do not ask an individual to read aloud or act as scribe without prior agreement.

- Be aware of visual, motor or auditory difficulties and use a multisensory approach: seeing, hearing and doing.

- Use visual props (flow charts, mind maps, charts, and diagrams, etc) to clarify points, as well as linear notes with bullet points, headings and subheadings.

- Allow breaks and vary activities to avoid information overload.

Selection/promotion assessments

Employers should establish what is essential for the role when an assessment process is being designed, an (EqIA) Equality impact Assessment should be initiated at this time to review each section of the process to ensure the widest group of candidates can meet the selection criteria.

Where an educational psychologist report is available and shared by an individual, this should be considered by the service when deciding on reasonable adjustments for each part of a selection process.

For example: There may be difficulties in people reading all written materials during assessment processes. Reading large volumes of text that require a response during an assessment centre should be reconsidered by services as a method of assessment.

People with Dyslexia tend to have a number of coping strategies which cease to work in certain circumstances, such as examination and assessments. The attributes associated with some dyslexia become much more visible when placed under the stress of having to perform a written task in front of an audience, and do not provide a true reflection of capabilities. These impairments ultimately affect the scoring mechanism during the promotions process and the allocation of posts. This possibility must be taken into account when assessing the effects of Dyslexia.

When placed in a challenging examination or assessment circumstances, a range of negative emotions may arise. This often results in low self-esteem and confidence, anxiety and confusion. Which in turn may have resulted in a discrepancy between academic achievement and performance in practical problem-solving and/or verbal skills.

Performance Management

Performance management places the emphasis on managing, supporting and developing staff at all levels in the Service. An integral part of this is the need to monitor performance, reward staff that perform well, and assist those who do not.

All adjustments must be considered in appreciation of individual circumstances.

Dyslexia and interviews: 5 tips

This is good practice for all interviews, but may be particularly helpful for individuals with dyslexia “”; change to “” in third bullet; “” – Reasonable adjustments policy and workplace needs assessment – would be

- Questions presented in written format with space to write notes

- Panel members read out to questions candidates and repeated this a number of times should be encouraged.

- Use of highlighters

- Voice the obvious answer first.

- It may be beneficial to offer candidates additional time.

- It is always helpful for candidates to let interview panels of any disabilities.

- Look through the job/course description carefully and think of possible interview questions they might ask you.

- It would be beneficial to add the Reasonable adjustments policy and workplace needs assessment as an appendix.

- Communities and Local Government – Integrated Personal Development System

Code of Practice

Spelling capacity

Dyslexia is a Specific Learning Difficulty (SpLD) that mainly affects reading and spelling. It is characterised by difficulties in processing word-sounds and by weaknesses in short term verbal memory; its effects may be seen in spoken language as well as written language. It is estimated about 10% of the population are affected by dyslexia to some degree, mainly in reading and spelling.

The way forward

Dyslexia is the most common neurodivergence, and most understood, usually affecting someone’s ability to read or write accurately. Dyslexia is a learning difficulty that primarily affects the skills involved in accurate and fluent word reading and spelling. It can also include challenges with information processing, short-term memory and timekeeping.

However, these challenges don’t stem from a deficiency in language, word processing or motor-control, they are the consequences of a unique brain processing function that means people with dyslexia often have a broad range of cognitive features and strengths too. The Exceptional Individuals provide comprehensive information on common dyslexic strengths, and links to video Dyslexia Course, including:

Supporting Links

Dyspraxia

Dyspraxia is a learning difference that affects how the mind processes actions, usually affecting coordination and movement. Dyspraxia is a specific learning difficulty affecting coordination, movement, balance and organisation abilities. Motor difficulties include poor hand to eye coordination and spatial awareness, which can make it difficult for people with dyspraxia to carry out everyday functions such as writing.

Dyspraxia is a specific learning difficulty affecting coordination, movement, balance and organisation abilities. Motor difficulties include poor hand to eye coordination and spatial awareness, which can make it difficult for people with dyspraxia to carry out everyday functions such as writing.

This neurodivergence often exhibits similar characteristics with other neurodivergent conditions, particularly Asperger’s Syndrome and ADHD, particularly in the areas of short-term memory, concentration, and social interaction.

Employees with dyspraxia are often extremely motivated, as they’ve had to persevere in the face of adversity all their lives. They are often strategic thinkers who have had to approach old concepts and problems with new, innovative ideas.

Workplace Needs Assessments for people with dyspraxia should be conducted to make sure they are you’re supported in the workplace.

Leadership – Dyspraxics often learn to develop soft skills such as active listening, empathy, and when to delegate tasks to others. Their desire for people to understand what they deal with ensures that they communicate clearly, too. All these result in dyspraxics making good leaders.

Empathy – Dyspraxics tend to have an innate ability to understand and respect what others are thinking or feeling. Their experience of struggling with things like coordination can mean they are empathetic when they see others in a tough situation.

Strategy – The learning difference does not affect a person’s IQ, but they may often have to navigate a mind which can be unorganized, meaning they are usually very intelligent people. Navigating around these barriers results in creating strategies to overcome problems in a structured way.

Problem-Solving – Dyspraxic people are great at coming up with different approaches to situations. Throughout school, dyspraxics find innovative ways to help themselves learn topics better, and this translates into working life, with dyspraxics being able to see alternative routes to others.

- Dyspraxia Course

- Dyspraxia course introduction

- How can dyspraxia affect you?

- Dyspraxia and mental health

- Famous people with dyspraxia

- Making it your USP

Autism

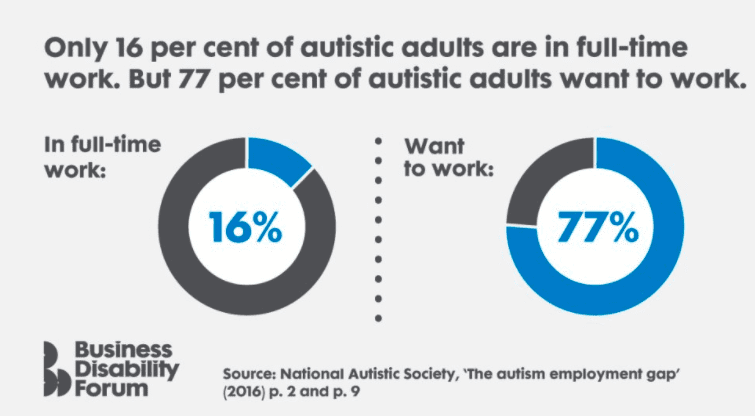

Autism is a spectrum condition which affects how people interact and communicate with the world.

Autism is a neurological developmental condition, characterised by repetitive patterns of behaviour and difficulties with social communication. Struggling to deal with change, mandatory actions, or other points of view can be elements of this learning difference.

No definition can truly capture the range of characteristics people on the autistic spectrum experience in a world often found to be “chaotic and illogical.”

There are many autistic people who have behavioural and communicative differences, but their intelligence is not impacted by their neurodivergence.

Common autistic strengths

Attention to Detail – Autistic people often have great attention to detail and focus. This means they may be able to search through a lot of information for specific content.

Efficiency – Autistic people can be very good at following rules, sequences and orders, meaning with the right structure can be very efficient.

Logical Thinking – Autistic people can be very logical thinkers, as they can struggle to consider emotional factors. This brings an innovative and objective approach to problem-solving.

Retention – Autistic people may be able to build encyclopedic knowledge on topics of interest, retaining lots of information. Visual memory is often also strong.

Common signs of autism in adults include:

- Finding it hard to understand what others are thinking or feeling

- Getting very anxious about social situations

- Finding it hard to make friends or preferring to be on your own

- Seeming blunt, rude or not interested in others without meaning to

- Finding it hard to say how you feel

- Taking things very literally – for example, you may not understand sarcasm or phrases like “break a leg”

- Having the same routine every day and getting very anxious if it changes

Other signs of autism:

- Not understanding social “rules”, such as not talking over people

- Avoiding eye contact

- Getting too close to other people, or getting very upset if someone touches or gets too close to you

- Noticing small details, patterns, smells or sounds that others do not

- Having a very keen interest in certain subjects or activities

- Liking to plan things carefully before doing them

Autism in women and men

Autism can sometimes be different in women and men.

For example, autistic women may be quieter, may hide their feelings and may appear to cope better with social situations.

This means it can be harder to tell you’re autistic if you’re a woman.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder ADHD

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder ADHD is characterised by inattentiveness, impulsivity and hyperactivity.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental condition that affects the nervous system, including the brain, during development from childhood to adulthood.

People with ADHD can experience impulsivity, hyperactivity, distractedness, and difficulty following instructions and completing tasks.

Since 1994, experts have used the term “Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder” to refer to neurodivergence that affects attention and concentration. However, some people do not experience hyperactivity and associated traits such as lower risk aversion or impulsivity.

The name “Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder” includes the forward-slash (/) between Attention-Deficit and Hyperactivity. This means that people diagnosed with ADHD could have either or both presentations (inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive). The presentations are:

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity: combined presentation

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity: predominantly inattentive presentation

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity: predominantly hyperactive-impulsive presentation

Those with this neurodivergence can bring energy and new approaches to the work environment. Unlike other neurodivergent conditions, the strengths of people with ADHD are usually a result of their ‘hard-wiring’ and not developed through challenges they face.

People with ADHD can have strengths of “hyperfocus” and “hyperactivity.”

Common ADHD strengths

Hyperfocus – People with ADHD can be very focused and committed to projects and tasks they are interested in, making them super efficient.

Creativity – The imaginative and busy minds of those with ADHD create original ideas and novel solutions to problems.

Enthusiasm – Despite periods of low energy, people with ADHD can have bursts of speed, enthusiasm and determination.

Innovation – The fearless approach that those with ADHD can often exhibit leads to bold, innovative ideas.

Other Neurodivergent Conditions

Below is a summary of some less-common learning differences, including links to simple tests to find out if you have specific neurodiverse characteristics. This list is not exhaustive, but will provide details about the most common conditions.

Dyscalculia

Developmental Dyscalculia is a specific learning disorder that is characterised by impairments in learning basic arithmetic facts, processing numbers and performing accurate and fluent calculations. Find out if you share Dyscalculia characteristics: Dyscalculia Test. This is an initial screening tool; please contact your manager or Human Resources if you identify as having this characteristic.

Dysgraphia

Dysgraphia is a specific learning disability that affects written expression. Dysgraphia can appear as difficulties with spelling, poor handwriting and trouble putting thoughts on paper. Dysgraphia can be a language based, and/or non-language based disorder. Find out if you share Dysgraphia characteristics: Dysgraphia Test.

Meares-Irlen Syndrome

Irlen Syndrome (also referred to at times as Meares-Irlen Syndrome, Scotopic Sensitivity Syndrome, and Visual Stress) is a perceptual processing disorder. It is not an optical problem. It is a problem with the brain’s ability to process visual information. Find out if you share Irlen Syndrome characteristics: Irlen Syndrome Test. This is an initial screening tool; please contact your manager or Human Resources if you identify as having this characteristic.

Hyperlexia

Hyperlexia is a syndrome observed in people who demonstrate the following cluster of characteristics: A precocious, self-taught ability to read words which appears before age 5, and/or an intense fascination with letters, numbers, logos, maps or visual patterns. Find out if you share Hyperlexia characteristics: Hyperlexia Test. This is an initial screening tool; please contact your manager or Human Resources if you identify as having this characteristic.

Tourette Syndrome

Tourette Syndrome is an inherited, neurological condition, the key features of which are tics, involuntary and uncontrollable sounds and movements. This is a complex condition, and many people with the condition may also experience other disorders or conditions, such as anxiety. Find out if you share Tourette Syndrome characteristics: Tourette’s Syndrome Test. This is an initial screening tool; please contact your manager or Human Resources if you identify as having this characteristic.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Obsessive compulsive disorder is a common mental health condition where a person has obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviours. Find out if you share Obsessive compulsive disorder. This is an initial screening tool; please contact your manager or Human Resources if you identify as having this characteristic.

Synaesthesia

Synaesthesia is a condition in which one sense (for example, hearing) is simultaneously perceived as if by one or more additional senses, such as sight. Another form of synaesthesia joins objects such as letters, shapes, numbers or people’s names with a sensory perception such as smell, colour or flavour. Find out if you share Synaesthesia characteristics: Synaesthesia Test. This is an initial screening tool; please contact your manager or Human Resources if you identify as having this characteristic.

Anxiety

Anxiety is a feeling of unease, such as worry or fear, that can be mild or severe. Everyone has feelings of anxiety at some point in their life. For example, you may feel worried and anxious about sitting an exam or having a medical test or job interview. Find out if you show signs of Anxiety Disorder. More information about Anxiety can also be accessed here. Anxiety disorder is a mental health condition and not a neurodivergent condition, but those with neurodivergent conditions often suffer from increased levels of anxiety.

This list is not exhaustive

Emotions following a diagnosis

Alongside the diagnosed symptoms of these conditions, there will also be an emotional component. While diagnosis during education is improving, many are diagnosed later in life, well into their careers. Below is the lived experience of these emotions from a member of the Civil Service Dyslexia and Dyspraxia Network, which are not uncommon fears:

- “Last week I was diagnosed with dyslexia. I’ve long suspected this, but it was a real shock when I was told. I was told I have lots of amazing skills, but I didn’t take in what was said.”

- “I feel like I am on an emotional rollercoaster. I now have an explanation about why I failed all those exams, why I feel like I am failing at work, and why I feel like I haven’t achieved my full potential.”

- “My diagnosis means I am disabled. I don’t feel disabled. I’m told it is a disability because of the impact it has caused by the way society is designed.”

- “Am I disabled enough to ask for adjustments? Surely, there are others more deserving?”

- “I’m not sure how to ask for adjustments”

- “Not sure what to ask for.”

- “Not sure that I will be taken seriously”

- “I don’t know what I am good at. No one has really told me before.”

- “It feels really personal. I don’t feel able to share.”

- “Sometimes I’m absolutely ok with it. Other times I really struggle to accept the diagnosis.”

- “All those messages of not good enough feel so real. I don’t feel able to share my diagnosis with my colleagues. I fear failure and being judged by others. I worry my career will be impacted. I have a deep, deep feeling of shame.”

Understand the strengths and challenges

Each individual has a different experience, with unique skills and challenges. A solution that works for one may not be the same solution that helps someone else. There are some things that neurodiverse people are really good at, and things that other people are better at. This can be a helpful way to explain strengths and weaknesses, as it can help keep the conversation positive.

Below are some examples of strengths neurodiverse people may have, and some things that are challenging. They are not exhaustive and do not necessarily apply to everyone. These positives and negatives are also situation-dependent, i.e. they might be different under assessment conditions. The list of strengths is also generic to apply to roles across Fire and rescue Service roles.

It can be good at:

- Coming up with ideas.

- Solving problems because seeing the situation from another perspective.

- Making unexpected connections.

- Spotting patterns and analytical skills.

- Storytelling.

- Thinking visually or in 3D.

- Diversity of thought.

- Remembering something connected which happened a long time ago.

- Finding the 3 relevant points in two pages of text.

- Imagining what the future looks like.

- Simplifying processes.

- Communicating verbally or presenting.

Sometimes other people are better at:

- Consistently being accurate with attention to detail.

- Writing in a ‘house style’.

- Reading aloud.

- Writing things by hand.

- Knowing how to structure a report or document.

- Following grammar rules and spelling.

- Remembering instructions.

- Following long processes or instructions with multiple steps.

- Remembering things – for example where a room is, the meaning of a word, or where they put something.

- Being tidy.

- Staying on task.

- Knowing instinctively how to use equipment.

- Not bumping into things they are close to.

- Not being easily distracted by sounds.

- Passing tests and assessments.

- Rote learning (remembering things by repeating them over and over again, like your times tables in maths).

How can you help

There are lots of ways you can help make things easier:

- Find information on your intranet or speak to your HR department and support through those processes to get the support/ adjustments that are needed.

- Keep an open mind.

- Be patient.

- Find out what they are good at, and don’t judge for what they are not so good at.

- Use manager discretion fairly, taking into consideration the conditions. Don’t be unnecessarily punitive where you don’t need to be.

- Have faith in your ability and strengths.

- Allocate tasks which suit our strengths.

- Don’t micromanage the way they do things, focus on the results.

- Recognise that some might have other neurodiverse conditions (for example autism, ADHD, bipolar disorder, Tourette’s syndrome).

- If performance measures are required, then take into consideration on conditions and adjust accordingly. The conditions may be the cause of poor performance, and adjustments may be a better course of action.

Access to Work can help to get or stay in work if you have a physical or mental health condition or disability. The support you get will depend on your needs. Through Access to Work, you can apply for:

- A grant to help pay for practical support with your work.

- Advice about managing your mental health at work.

- Money to pay for communication support at job interviews.

Practical support with work

Access to work could give a grant to help pay for things like:

- BSL interpreters, lip speakers or notetakers.

- Adaptations to your vehicle so you can get to work.

- Taxi fares to work or a support worker if you cannot use public transport.

- A support worker or job coach to help you in your workplace.

Your workplace can include your home if you work from there some or all of the time. It does not matter how much you earn. If you get an Access to Work grant, it will not affect any other benefits you get, and you will not have to pay it back.

You or your employer may need to pay some costs up front and claim them back later.

How to apply

Check you’re eligible and then apply for an Access to Work grant.

Things to remember

It can be challenging, but try to remember:

- Everyone is unique – that includes our skill sets.

- One size does not fit all – what works for one might not work for someone else.

- We will bring something different to the team.

- They sometimes know what works best for them, so ask if help needed – but they may not always have a solution or fully understand the challenges.

- Learning about our challenges is ongoing. New situations can make challenges more obvious, especially when existing coping strategies no longer work.

- They might approach a task in a different way – it might be the only way they can do it, but they might also find an improvement to the existing way.

- Like everyone, they will have good days and bad days.

- Try to be generous for grey areas or use line manager discretion.

- Keep information about a diagnosis and any adjustments private, and don’t discuss them without permission.

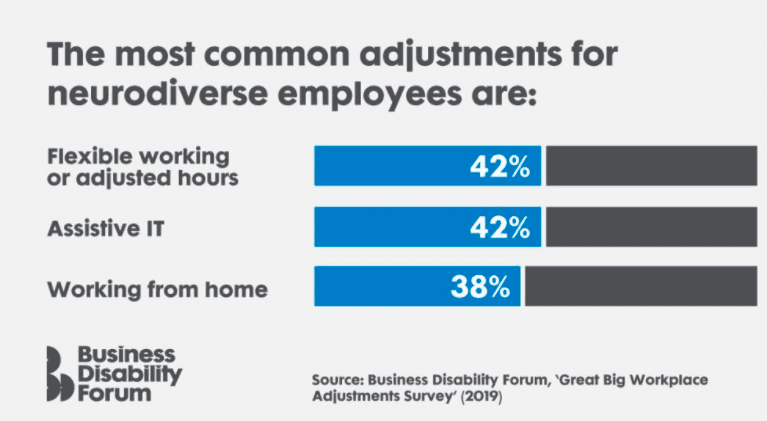

Support workplace adjustments

Workplace adjustments include anything that makes it easier for you to do your job.

To get an adjustment, you might need to go through a workplace needs assessment.

Adjustments can be obvious and may have a cost, but most are either free, or very low cost. They might not resolve a problem entirely, but they do reduce barriers in the workplace.

Examples of workplace adjustments

There are many adjustments that can be made, and some are challenging in the context of the sector, but you should endeavour to support as many as you can. For example:

- Using technology or alternative equipment.

- Allowing for extra time to read documents or to complete work.

- Traditional assessment methods may not work for some. Consider alternatives.

- Redesigning of a job role (known as job carving).

- Not expecting someone to answer other people’s phones.

- Giving tasks to people that suit their strengths.

- Using noise reducing headphones to help focus by reducing distractions.

- Switching off certain lights in an office.

- Providing quiet workspaces.

- Allowing someone to have a fixed desk every day instead of hot desking.

- To have a fixed desk with a wall behind and/or to the side to help focus.

Examples of technology adjustments

Technology adjustments can be simple, including:

- Using screen reader technology.

- Using dictation software to create documents, such as Dictate or Immersive Reader functions in Office 365.

- Using Microsoft Accessibility Technology tool.

- Mind mapping (either by hand or using digital software).

- Using Google Keep or Microsoft OneNote to organise reference material in one place.

- Using advanced grammar and spell checkers.

- Changing your monitor settings.

- Increasing text size.

- Changing the background colour to reduce visual stress.

- Using two monitors instead of just one.

There are also more suggestions for adjustments in:

• the British Dyslexia Association.

• the Dyspraxia Foundation’s workplace guidelines.

Requesting workplace adjustments

Even if someone has not had a formal diagnosis, they are still entitled to workplace adjustments in the workplace. A way of supporting staff is to create a method in which adjustments can travel with the employee throughout their career and or the organisation, similar to a passport. The purpose of the Workplace Adjustment Passport is to capture all agreed workplace adjustment requirements of employees, whether it be physical or non-physical. The aim is to minimise the need to re-negotiate workplace adjustments every time an employee moves post, moves between departments or is assigned a new line manager. This document belongs to the employee and their line manager should have a copy.

The proposal is to support staff wishing to move between departments or promotion processes, support well-being but not having to undertake a reassessment during a transition.

Requesting adjustments or other conversations with HR should be made in private. Some adjustments you can agree with your line manager, and there will be others that you need to contact Human Resources or your adjustments service to arrange. It is recommended that signposting for colleagues should be made readily available.

An example of a completed workplace needs adjustment and passport can be accessed here.

Specific Workplace Challenges – Sample Case Studies

This is to provide you with some examples and solutions however, adjustments would need to be made in line with services procedures.

Background noise and the work environment

The employee is experiencing sensory overload, and they can be easily distracted by things, some examples and solutions that Services could use are set out below:

It should also be noted that adjustments should reflect Service needs and procedures.

- Different conversations happening at the same time.

- Typing from other computers.

- A draft from an open window.

How managers can help

- Give them a desk away from printers and other machines or technology that make noise.

- Allow them to work from home if possible.

- Arrange for them to sit at a desk that other people cannot walk past.

Things individual can do

- Change their working hours so they’re in the office when it’s quieter (early mornings or later evenings).

- Structure their day so they can work on tasks which need concentration during quieter times.

- Managers could arrange with their teams that a specific time of the week is for reading.

- Use headphones to reduce external noises (remember that noise-cancelling headphones only reduce the sound – they don’t eliminate sound).

Following instructions

The member of staff finds it difficult to remember all the things their manager listed. Later, the manager asks for their progress. The employee explains they could not remember what they were asked to do, so have only done part of one of the tasks.

What is really happening?

The line manager is giving a long list of requests and instructions all at once. The employee has found it difficult to process everything and is therefore unable to recall all of the instructions.

How can managers help?

- Break requests down to one or two at a time – this makes them easier to remember.

- Put requests in writing, so they do not need to be remembered.

- Clarify what the asks are – ask the individual to feedback what they are tasked to do.

Practical tasks

A manager asks an employee to complete an Operational task or perform and organisational task. The employee finds these difficult and is worried about admitting this.

What is really happening?

The employee has dyspraxia, or developmental coordination disorder (DCD), and finds it difficult to do things that other people may consider simple. They fear ridicule for not being able to use routine equipment that society believes is easy to do.

How managers can help

- Understand that some simple, everyday tasks can be challenging or even impossible.

- Operational teaching methods can be modified to a person’s needs, ensuring standers are maintained.

- Offer alternative equipment to use.

- Attach step-by-step instructions to things like printers or other equipment.

- Allow an untidy desk or make an exception to a hot desk policy -sometimes it’s the only way they can remember where things are.

- Provide additional physical or electronic storage, so they don’t have to remember as much information.

Things individual can do

- Stand beside the person showing you a new practical task. This will let you know what side of your body to use. This will help make the task a little easier.

- Highlight to managers methods of learning that work best.

Reading

An individual is being asked to read a document and respond urgently with their thoughts in writing.

What is really happening?

The individual finds it difficult to process everything and may skip parts or not read them properly. They feel pressure to respond quickly, and this means their response isn’t communicated clearly or involves grammatical or spelling errors.

How managers can help

- Establish what the individual needs in terms of time to read, reflect and write up their thoughts.

- Offer to unpack the question. A colleague could help with this.

- Where possible, give reactive work, which doesn’t have a tight deadline.

- Give warning in advance if possible, to help them plan their time.

- Create templates and materials that can be reused.

- Don’t demand a verbal response – reading aloud can be difficult.

Recruitment and applications

A person has received a number of feedback letters from jobs they have applied for. Each letter tells them that they should have done something in their application differently.

What is really happening?

The applicant doesn’t understand the unwritten rules around recruitment, such as how to format an application answer or present their strengths.

Building an application is difficult due to the time taken. This is affected by working memory and difficulty to process the information and apply within a limited timeframe. This can lead to fatigue and the usual coping strategies eventually stop working.

Challenges of job applications

There are many challenges people with neurodiversity issues face during the recruitment process:

Considering applying for a job

- Not feeling confident at about what your strengths

Looking for a job

- Potentially misunderstanding what the job will entail from the advert

Application form

- Word count limitations.

- Time pressures.

- Takes a long time to write an example, but it may not be pitched correctly or explained well.

Tests

- Tests can highlight weaknesses.

- Extra time may be required.

- May need to read the instructions many times for comprehension and to remember what was required (working term memory).

Interview

- Telling a story in a format.

- Remembering the aspects of the story to highlight without going on a tangent.

- Notes don’t make any sense when you are mid-conversation.

- You’ve forgotten the question – it’s not a natural conversation.

Not progressing

- Impact on confidence and wellbeing from cumulative rejection.

Throughout the process

- Misunderstanding or misinterpreting what is expected.

- Usual coping strategies don’t work.

- Organising thoughts and forgetting them before they are written or spoken.

- Implied requirements and criteria not expressed to the applicant.

- Doing tasks not used in everyday tasks.

- In other settings, I would usually get opportunities to learn how to do a task in a way that works for me. In a recruitment process, I don’t get this.

- You may see me at my worst, not my best.

Some examples for that can support the manager and person during the interview.

How managers can help

- Offer extra breaks during the interview, so the applicant does not feel rushed.

- Allow some extra time for the interview to allow the applicant to refocus.

- Assess applicants in other ways, such as job shadowing a current team member instead of an interview.

- Use a show and tell format, so the applicant can discuss their work and achievements without it feeling like a formal interview.

- Provide interview questions in advance and provide them in writing during the interview.

- Think about the tasks included in the job advert – if they aren’t done very often, consider not including them in the job description.

Things individual can do

- Present their story visually.

- Use notes during the interview.

- Practice techniques and delivery in advance.

- Allow applicants to attend assessment centres across two or three days.

- Provide additional time before and during an interview or assessment.

Social situations, meetings and conferences

An individual is in a meeting, workshop or conference. They aren’t sure how they can contribute to the discussion as they find it difficult to fully understand what is being said, so they can’t judge when to join in.

What is really happening?

- They are showing signs of sensory overload, with lots of things happening at once.

- There are multiple conversations, and different tasks to think about, with no opportunity to prepare in advance.

- They may also not be comfortable in a large social setting.

How managers can help

Before the event:

- Put up visual signs around the venue – say things like go past the canteen rather than turn left.

- Avoid icebreaker activities (most of them require use of working memory).

- Use the largest text size possible – this means using more slides with less information (which is a good thing).

- Font Arial 14 is a clear typeface and size for documents.

During the event:

- Keep task instructions visible (digitally or printed) so people don’t need to remember what they are doing.

- Try to limit instructions to 2 at a time.

- Don’t put people on the spot to answer questions.

- Provide small quiet spaces at large workshops or conferences.

- Offer extra breaks, so people can regroup and focus.

- Look around for anyone who looks like they may need help.

- Offer help discreetly.

After the event:

- Accept contributions or feedback after the event, as well as on the day.

Things individual can do

- Prepare a few words to explain to others that they need to take a moment to regroup.

- Use visuals.

Staying on task

- An individual has been trying to get some of their tasks done but is becoming distracted easily.

- They are aware that they have been working for some time and have not actually completed any tasks.

What is really happening?

The individual is experiencing sensory overload, stopping them from concentrating. Their working memory does not allow them to remember all of the information needed to think about a large number of tasks at once. This is making them even more stressed, and mentally tired, so they are even less able to concentrate.

How managers can help

- Offer to help prioritise their list of tasks.

- Suggest completing smaller quick jobs that can be easily completed before tackling bigger tasks.

- Consider a workplace needs assessment.

Things individual can do

- Recognise when you are not able to concentrate and try to slow down.

- Prioritise the list of tasks.

- Consider using a timer (such as tomato timer) to break down work into smaller tasks

- Consider doing quick jobs that can easily be completed before tackling bigger tasks.

- Take a short break if they feel overloaded.

Wellbeing at work

A line manager is out of the office and asks to speak with an employee when they return. They do not say why they want to speak to them.

What is really happening?

Past experience tells the employee they have done something wrong, which impacts on their wellbeing and self-worth. They assume something negative is going to happen.

How managers can help

- Be clear about the reasons you want to meet with people – this will stop them worrying unnecessarily.

- Try to focus on the person’s strengths, not their weaknesses.

- Encourage people to seek support for their wellbeing and ask for help whenever they need it.

- Keep discussions about their diagnosis private, and only share information with consent.

- Don’t make assumptions or judge the impact of the diagnosis.

Things individual can do

- Consider adding a short note in their email signature to explain why their spelling or grammar may not be perfect.

- Be open with their manager so any increase in difficulties or stress can be more easily spotted.

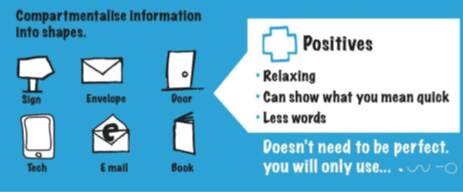

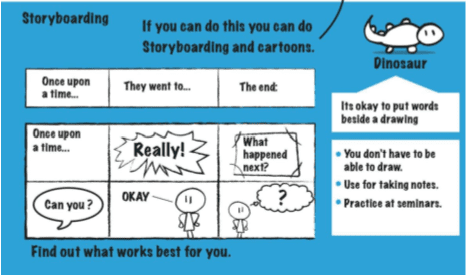

Working visually

Creativity and big picture thinking are likely key factors in the extraordinary link between dyslexia and entrepreneurship. Other notable traits of dyslexic people may also contribute to this – such as an ability to create a vision through visual narrative thinking and then use this vision to inspire others through powerful storytelling. Dyslexic people may also be comfortable with risk-taking, and – like other neurominorities – may also have developed resourcefulness and problem-solving skills from having to navigate a world shaped largely for neurotypicals.

There are many ways that working visually can help. Images are processed faster than words and can be remembered more easily too. You could try:

- Drawing things that are part of a process, so you can use fewer words.

- Simplifying your drawings – they can be as basic as you want.

- Using a storyboard – this is a good way of splitting a big process into smaller parts.

- Adding a word or two to describe your drawing – it’s still simpler than using words without pictures.

You don’t need to be good at drawing. It’s more relaxing to draw than write, and it’s sometimes a quicker way of making notes than using words.

Working in hazardous conditions

An individual is worried that their condition puts them at risk of having an accident at work.

What is really happening?

The individual has a combination of diagnoses that may increase the chance of something going wrong when working in hazardous conditions.

They may have dyspraxia, affecting their movement and balance, or have challenges with their working memory or processing speed.

They may also find increased difficulty when the order of tasks has changed.

How managers can help

- Create a quick reference guide that makes following long processes easier.

- Look for ways of working which will suit the individual and also achieve the end goal.

- Consider a workplace needs assessment.

Things individual can do

- Think about processes and consider where the challenges may be.

Writing

An individual is concerned their report is significantly shorter than they think it should be. Their writing style does not fit with the organisation’s ‘house style’.

What is really happening?

The team members face literacy and sequencing challenges. They may be missing out letters or words, repeating certain words or mixing up the order. This can make it harder for them to write the document and also to read it to check for any errors. They may not know about certain grammar rules, or there may be too much structure in the document.

How managers can help

- Ask for advice about what is requested in advance, and leave plenty of time for writing the document before the deadline.

- Understand that it might take time to learn a task.

- Give clear information about what you are expecting – for example how long it should be, the format, the structure.

- Provide a previous example for reference.

- Create template documents that have the required structure and format.

- Consider whether everything you think needs to be corrected is essential.

- Agree with the individual and a buddy to assist with sense checking or corrections.

- Don’t use a red pen to correct errors.

Things individual can do

- Find a quiet place to work away from their desk.

- Use software to dictate the tasks or advance spellcheckers.

- Use an online thesaurus or software such as Grammarly when you need to find an alternative word.

- Set out the things they want to write about, and work on the structure later – consider using mind mapping (written or digital).

- Arrange for someone to help check the document.

Jargon buster

Auditory or visual processing

Some adjustments may be helpful if auditory or visual processing speed is a strength. Using software to listen to text may be easier than reading the text. This would not benefit those with poor auditory processing.

Processing speed

This is the part of the brain that recalls information when receiving information from another source. An example of this would be finding the word you are looking for. Some people are quicker than others at this.

Sensory overload

- Sensory overload is being sensitive to sensory information, including blocking out noise.

- Some people are more sensitive to sensory information.

- Some examples of this are being unable to concentrate in an open-plan office, reacting to high-pitched noises, and finding some textures problematic.

Short-term memory

The part of the brain you use for holding information quickly

An example would be a colleague giving you their telephone extension number, then remembering the number long enough to dial the number.

Visual difficulties

- Visual difficulties are where there are visual symptoms. Although not connected to dyslexia, some will experience symptoms.

- It is when there are visual symptoms, including words moving around the page or the appearance of rivers of white between the words.

- Different coloured paper and backgrounds on the screen can help. Visual stress is diagnosed by an ophthalmologist or a behavioural optometrist.

- There is no connection between visual difficulties and dyslexia, but they can be experienced by some people with dyslexia.

Working memory

This part of the brain is used for holding information quickly then doing something with this information, such as doing mental arithmetic.

A good way to explain this is to think of the memory as a shelf:

- Someone with a regular memory has a shelf that’s 1 metre long.

- Someone with less working memory has one that’s 10 cm long.

This makes it difficult for the person to remember facts and get them out of their brain.

Workplace adjustment passports – sample process

The purpose of the workplace adjustment passport

The Workplace Adjustment Passport was originally developed and introduced by the Civil Service in response a Talent Action Plan in 2015, which recommended a single adjustment passport for all departments. It is a recommended practice aimed at supporting employees with a disability, health condition or those who are undergoing gender reassignment in the workplace.

The passport has three main functions:

- To support a conversation between an employee and their line manager about the disability, health condition or gender reassignment and any workplace adjustments that might need to be made.

- To act as a record of that conversation and of the adjustments agreed.

- To act as a record of any adjustment made for individuals as supportive measures.

The passport will be particularly helpful when the employee changes line manager, as it will help the new line manager to understand what workplace adjustments the employee had been receiving previously and avoid the need to begin the process again.

It can also be helpful in starting a conversation about less visible disabilities, such as mental health conditions. The first section of the passport focuses on information that may help a line manager to understand more about an employee’s disability, health condition or gender reassignment and the barriers experienced. The next section focuses on the impact (if applicable) of an employee’s disability, health condition or gender reassignment on their daily working life and specific requirements or adjustments identified to overcome any barriers.

The workplace adjustment passport application process

Individual responsibilities

Completion of the passport is voluntary. You have control over the content and who it is shared with. You retain ownership of the form throughout. Complete your personal details in the box provided, include as much detail as you feel is appropriate. Share a copy of your passport with your line manager and discuss the details so that they can understand how to support you.

A discussion will give you the opportunity to explain to your line manager the issues you have identified. Whilst it is up to you to decide how much to tell your line manager about your disability or health condition and how it affects you, sharing information can help them to better understand something that they may be unfamiliar with and how they can support you.

Any actions agreed and review dates should then be entered on the passport and shared with your line manager. You may also want to discuss the contents to appropriate contacts such as a Fire Warden, Mental Health First Aider or buddy.

If your circumstances change e.g. due to your disability, health condition or gender reassignment, you should update the passport and speak to your line manager to discuss any impact on your workplace adjustments. Adjustments should be reviewed when there is a change or at least every 12 months. The passport should be updated to reflect any agreed changes in your adjustment requirements.

Line manager responsibilities

The sector aims to create an inclusive environment in which employees are confident that they can disclose information about their disabilities, health conditions or gender reassignment, to those with whom they work without fear of discrimination or harassment.

Your role as a line manager is to create an inclusive culture where people are comfortable sharing information with you. Your actions and decisions are of great importance in considering any steps which might be taken to assist an employee in their work. The passport is designed to support you to do this. The sector also has responsibilities to their employees under the Equality Act 2010. As a line manager, it is your responsibility to understand and comply with the requirements.

Line managers should treat the information contained in the passport and discussions with individuals about their disability, health condition or gender reassignment in the strictest of confidence.

It is important to remember that the passport belongs to the employee and is confidential. If you move to another post you should not pass the form to the next line manager without the employee’s permission, or if the employee moves post, send it to the new line manager without consent.

When you receive a passport from an employee, you should arrange a one-to-one meeting with them as soon as possible.

It is for the individual to decide how much to disclose about their particular disability, health condition or gender reassignment. However, it is important that as a line manager, you are able to understand how it affects their day-to-day work and what you can do to support and assist them to succeed.

Line managers have a responsibility to ensure that anyone wishing to complete the passport is given adequate official time to do so. You may require specialist help when identifying appropriate workplace adjustments. Where necessary, you should seek advice, particularly about mental health issues, complex disabilities or gender reassignment where the effects on work may be difficult to predict.

In the first instance, you should refer to your departmental Workplace Adjustment team, who will suggest other sources of support if necessary.

- Understanding the impact of the disability, health condition or gender reassignment can help you to agree, with the employee, which adjustments are most practical and appropriate.

- If your employee’s circumstances change, such as due to their disability, health condition or gender reassignment, you should advise them to update their passport and discuss any impact on workplace adjustments.

Adjustments should be reviewed when there is a change or at least every 12 months. The passport should be updated to reflect any agreed changes in your employee’s adjustment requirements.

Further information about workplace adjustment passports

Additional guidance on supporting employees can be found in:

- Your department’s Workplace Adjustment guidance.

- The List of Common Workplace Adjustments.

- The Workplace Adjustment Line Manager’s Best Practice Guide.

- The Line Manager’s Best Practice Guide for Supporting Disabled Employees.

Example of a completed workplace adjustment passport form

The purpose of the passport is for you to record all workplace adjustment requirements agreed with your line manager. Sharing and discussing your passport with your line manager can enable them to provide you with tailored support and appropriate workplace adjustments. Below is an example of what the completed passport could look like.

Workplace Adjustment Passport – Personal when completed

Name: Mickey Ford

Name of line manager: Simon Horse

Details of your disability, condition or barriers you currently experience

This section should include information that may help your line manager to understand the impact your disability, health condition or gender reassignment has on your life, do not list anything that you do not feel comfortable disclosing.

Mickey:

- Have received a diagnosis of dyslexia and dyspraxia, and in my previous employment was supported with some workplace adjustments.

- I have difficulty concentrating when there is a lot of background noise. I find that I have to keep checking my work to ensure that I have completed it correctly.

- I find reading documents with a white background quite difficult.

- I do need extra time to support me undertaking tasks.

- I do sometimes have low self-esteem if it is assumed that I cannot do my work properly or slowly.

Details of how this affects you at work and the support you need:

This section could include:

- The aspects of the job where you experience barriers and require adjustments. This could include the work environment, communicating with others, working arrangements or equipment.

- Any specific requirements such as altered lighting, sitting away from draughts or near to toilets. These adjustments may be in place now, but this may alter if your accommodation changes.

- Specific adjustments you already use or know you need, for example screen reading software to convert text to speech already installed on your laptop or flexibility in start and finish times.

- How these adjustments will help you or remove the barriers identified you have included.

Mickey:

- Find natural light helpful and not the glare of bright lights.

- I use assistive software on my laptop at home that may be beneficial for this workplace. I have the latest Dragon software, although this may not be good in a noisy environment.

- I do need extra time to complete my work and feel that I would benefit from a buddy in the first few weeks to help me adjust to the work.

- It would be really helpful if I could have any documentation to read prior to any training or meetings, and time allocated after a team meeting to ask any questions about what was discussed.

- I find it easier to view documents on a mint coloured paper.

- I can adjust this colour for myself in Microsoft applications.

- I may need a screen filter to be purchased.

Additional information:

This section could include:

- Details of any recent assessments for Occupational Health, Display Screen Equipment or Workstation.

- Information about help you may need to evacuate a building in an emergency and whether you have a Personal Emergency Evacuation Plan. Contact details of someone to get in touch with in case of an emergency.

- Information about any plans you have in place such as a Wellness Recovery Action Plan or what your line manager and/or colleagues should do if you feel unwell.

- Details of anything else you think would be useful.

Mickey:

- I have completed the ergonomic desk assessment and the chair and desk are ok.

- My monitor is a bit on the small side, would it be possible to have a bigger one? When I increase the font size on my current monitor, all of the screen starts to go off to the side and I am forever scrolling sideways, and that adds time to my processing.

Details of agreed workplace adjustments form

| Adjustment including personal workaround they do that could be adopted | Date identified | Date implemented |

|---|---|---|

| Given a desk near a window and away from lights | [enter date] | [enter start date or notice date] |

| Dragon software installed on laptop

Agreed that documents for meetings or training will be provided at least 2 days in advance |

||

| Arranged a buddy for training during the first month, and review at the end of the month | ||

| Can we make sure form is not limiting, perhaps the person has a work around they do that could be adopted for them legitimately. |

The following table is used to keep a written record of when the passport is reviewed or amended.

| The passport should be reviewed every year REVIEW DATE | |

| Employee signature | Date |

| Line manager signature | Date |

| Amendments made | Date |

| Reason for amendment | Date |

This document contains personal information, which should be stored in accordance with the Data Protection Act 2018 and your Service document retention policy.

Dyslexia Risk Assessment Form – Example

- Download the Dyslexia Risk Assessment Form – Example

Proposal for support for employees with Dyslexia requirements

In implementing the Disability Action Plan, NIFRS Diversity Officer has researched the area of Dyslexia and its impacts on NIFRS in terms of appointments, promotions, training and performance management. This work will also contribute to the Disability Equality Policy and the Recruitment and Retention of Disabled Employees (all staff). A list of training and sources of research is contained in the Appendix.

What is dyslexia?

Dyslexia is a Specific Learning Difficulty (SpLD) that mainly affects reading and spelling. It is characterised by difficulties in processing word-sounds and by weaknesses in short term verbal memory; its effects may be seen in spoken language as well as written language. It is estimated about 10% of the population are affected by dyslexia to some degree, mainly in reading and spelling.

People with dyslexia usually find it difficult to process the sounds of spoken words, and some may have difficulties with short-term memory, sequencing and organisation. The ability to map spoken words by their letter-sequence is impaired, which affects the ability to spell and the ability to decode or “sound out” words. Although many people with dyslexia can learn to use phonic decoding skills, they typically need an increased level of instruction, and they often never reach a stage where these skills are fully automatic.

Dyslexia is not the same as a problem with reading. Many people with dyslexia learn to read but have continuing difficulties with spelling, writing, memory and organisation. There are also people whose difficulties with reading are not caused by dyslexia. Dyslexia often causes problems in maths; many have difficulties with arithmetic and with learning and recalling number facts.

The degree to which dyslexia causes problems, in learning and in everyday life, depends on many factors. These include the severity of the dyslexia, the other strengths and abilities that a person has, and the kind of teaching and support they may have been given.

Dyslexia may show itself in a variety of ways, as shown below. It is most unlikely that all the characteristics would be evident in one person;

- A discrepancy between academic achievement and real-life performance in practical problem-solving and verbal skills

- Taking much longer to read a book and understand it

- Missing off endings of words in reading and spelling

- Poor presentation of written work, poor spelling and punctuation

- Not being able to think what to write

- Reluctance to write things down

- Confusing telephone messages

- Difficulty with note-taking

- Difficulty in following what others are saying

- Difficulty with sequences

- Reversing figures or letters or omitting words

- Problems with time-management

- Trouble with remembering tables

- Difficulty with mental arithmetic

Best practice approach to managing dyslexia in the workplace

Joint Council for Qualifications guidance on dyslexia in national

examinations:-

For candidates/employees with learning difficulties or comprehension disorders

A diagnostic assessment of reading, comprehension, writing, spelling or cognitive processing as appropriate should be made in order to decide on appropriate access arrangements. An Educational Psychologist Report is the usual method of confirming a diagnosis of dyslexia. In many cases, an individual will already have a diagnostic assessment from their time at school. However, some individuals will have been assessed. The validity of these assessments will vary, depending on whether up to 25% extra time is being requested or a reader or scribe is needed. Where only 25% extra time is required, a ‘Statement of Special Educational Need’ or a diagnostic report which relates to the secondary school period will still be valid and should be requested to confirm the validity of the request.

Examples of how access arrangements for ‘extra time’ would apply

Where a candidate has been assessed as having a ‘moderate dyslexic condition’, affecting speed of processing, he or she may be allowed up to a maximum of 25% extra time, depending on need, to finish writing examination papers.

Examples of how access arrangements for a ‘reader’ would apply

Where a candidate is assessed as requiring a reader in examination/assessment conditions, this person would be a responsible adult who reads the questions to the candidate. This may involve reading the whole paper to the candidate, or the candidate may request only some words to be read. A reader is not a scribe, but may act as both reader and scribe as long as permission has been given for both arrangements.

The reader will not be allowed where sections of the paper are designed to test reading. A candidate who would normally be eligible for a reader but is not permitted this arrangement due to the structure and content of some examinations may be granted additional time allowance.

The reader should not normally be the candidate’s relative, friend or peer of the candidate. The provision of a reader should reflect the candidate’s normal way of working, except in cases where temporary injury gives rise to the need for a reader.

In examination/assessment situations, readers may work with more than one candidate, but must not read the same paper to a group of candidates at the same time, as this imposes the timing of the paper on the candidates. Where candidates require only occasional words or phrases to be read, three or four candidates may share one reader. The candidate would need to raise his or her hand when needing help with reading. If the group is accommodated separately, a separate invigilator will be required. Centres whose candidates are not permitted a reader should accommodate candidates separately so that they may read aloud to themselves.

A reader must;

- Read accurately

- Must only read the instructions of the question paper(s) and questions, and must not explain or clarify;

- Must repeat instructions given on the question paper only when specifically requested to do so by the candidate;

- Must abide by the regulations, since failure to do so could lead to the disqualification of the candidate;

- Must not advise the candidate regarding which questions to do, when to move on to the next question, nor the order in which the questions should be answered

- Must not decode symbols and unit abbreviations

- Must not provide factual information nor offer any suggestions, other than that information which would be available on the paper for sighted candidates;

- May read numbers printed in figures as words

- May read back, when requested, what has been written in the answer;

- May, if requested, give the spelling of a word which appears on the paper, but otherwise spellings must not be given.

Examples of how access arrangements for a ‘scribe’ would apply

Where a candidate is assessed as requiring a scribe in examination/assessment conditions, a scribe should be provided in subjects testing written communication skills, including English. However, the candidate will be assessed only on those subjects of written communication which he or she can demonstrate independently, such as the use of language, effective and grammatical presentation. If separate marks are awarded for spelling and punctuation, these cannot be credited to a candidate using a scribe. Marks may be awarded for punctuation if this is dictated, and the fact is noted on the scribe cover sheet.

The provision of a scribe should reflect the candidate’s normal way of working. A scribe: